Eesti teadlased Andreas Kalkun ja Kersti Lust uurisid

vallasemade elu

. Nad leidsid, et 19. sajandil ei olnud vallasematel kerge. Kirikuraamatute ja kohtudokumentide järgi olid nende lapsed sageli häbiks. Meedias on aga levinud teistsugune arvamus, et eesti külas üksikemasid ei põletatud.

vallasemade elu

Tõlge fraasile: vallasemade elu

EN

life of unwed mothers

Varasemad uurijad väitsid, et üksikemasid ei põletatud. Kalkun ja Lust aga leidsid, et vallasemade põli oli kibe. Nad uurisid erinevaid allikaid, nagu folkloor,

kirikuraamatud

ja

kohtudokumendid

. Nende järgi olid vallasemad sageli häbistatud ja nende lapsed nimetati halvustavalt.

kirikuraamatud

Tõlge fraasile: kirikuraamatud

EN

church records

kohtudokumendid

Tõlge fraasile: kohtudokumendid

EN

court documents

Folklooris kutsuti vallasemasid halvustavate nimedega, näiteks "hoor" või "lits". Nende lapsi nimetati "

hoora- või litsilasteks

". Kristlik kultuur mõjutas ka sõnakasutust, kus üksikema lapsi kutsuti "

häbilasteks

".

hoora- või litsilasteks

Tõlge fraasile: hoora- või litsilasteks

EN

as children of whores or sluts

häbilasteks

Tõlge fraasile: häbilasteks

EN

as children of shame

Kirikuväravas pandi vallasemaid häbiposti ja neid peksti. Sellised karistused kaotati 18. sajandil, kuid 20. sajandilki juhtus veel selliseid juhtumeid. Näiteks Kahala külas pidid tüdrukud vallaslastega istuma kirikus

altari ees

ja neile võidi sülitada.

altari ees

Tõlge fraasile: altari ees

EN

in front of the altar

Ka kirjanduses on vallasemate elu kujutatud kurbana. Näiteks Juhan Liivi teoses "Varju" on üksikema traagiline. Samuti kirjeldad Helmi Mäelo oma teostes, kuidas üksikemad ja nende lapsed kannatasid.

Uuring näitas ka, et üksikemadel oli

raske mehele saada

. Nad abiellusid sageli vanade või vaesete meestega. Sellepärast leppisid nad tihti leskede või erusoldatitega. Alles pärast laste surma said nad tihti uue kaasa. Ka vallaslaste

abieluväljavaated

olid kehvad kuni 1890. aastateni.

raske mehele saada

Tõlge fraasile: raske mehele saada

EN

hard to find a husband

abieluväljavaated

Tõlge fraasile: abieluväljavaated

EN

marriage prospects

Kokkuvõttes oli üksikemate elu eesti külas väga raske. Nad

kogesid häbi ja vägivalla

. Seda kajastavad mitmed ajalooallikad.

kogesid häbi ja vägivalla

Tõlge fraasile: kogesid häbi ja vägivalla

EN

experienced shame and violence

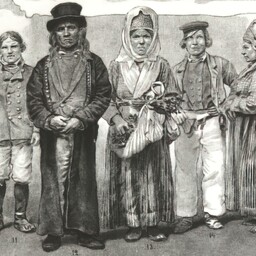

Estonian researchers Andreas Kalkun and Kersti Lust studied the lives of unwed mothers. They found that in the 19th century, unwed mothers did not have it easy. According to church books and court documents, their children were often a source of shame. However, a different opinion has circulated in the media, claiming that unwed mothers were not burned in Estonian villages.

Earlier researchers claimed that unwed mothers were not burned. Kalkun and Lust, however, found that the fate of unwed mothers was bitter. They studied various sources, such as folklore, church books, and court documents. According to these, unwed mothers were often shamed, and their children were called derogatory names.

In folklore, unwed mothers were called derogatory names, such as 'whore' or 'slut.' Their children were called 'whore's children' or 'slut's children.' Christian culture also influenced language use, where children of unwed mothers were called 'children of shame.'

Unwed mothers were placed in the pillory at the church gate and beaten. Such punishments were abolished in the 18th century, but similar incidents still occurred in the 20th century. For example, in Kahala village, girls had to sit in front of the altar in church with unwed mothers, and they could be spat on.

In literature, the lives of unwed mothers have also been portrayed as sad. For example, in Juhan Liiv's work 'Shadow,' the unwed mother is tragic. Similarly, Helmi Mäelo describes in her works how unwed mothers and their children suffered.

The study also showed that unwed mothers had difficulty finding a husband. They often married older or poor men. Therefore, they often settled for widowers or discharged soldiers. Only after the death of their children did they often find a new spouse. The marriage prospects of unwed mothers were also poor until the 1890s.

In conclusion, the life of unwed mothers in Estonian villages was very difficult. They experienced shame and violence. This is reflected in several historical sources.